From the very beginning, it was difficult to get anyone to care about this amazing technology. A few months after the first ARM chips were shipped, Steve Ferber of Acorn Computers called a tech reporter and tried to get him to tell the story. The reporter replied “I don’t believe you. If you were doing this, I would know. Then he hung up.

While Acorn struggled, Ferber tried to imagine how the ARM chip could be spun off into a separate company. But he couldn’t figure out how to make the business model work. “You have to sell millions before the royalties start paying the bills,” he said in an interview. “We couldn’t imagine selling millions of these things.”

The future looked bleak until another computer company came through the door. A small company called Apple.

New company

How did Apple even know about ARM? Two engineers from the Apple Advanced Technology Group, Paul Gavarini and Tom Pittard, built a prototype computer called Möbius. It used an ARM2 chip and ran Apple ][ and Macintosh software, emulating the 6502 and 68000 processors faster than native versions. Apple’s senior management was baffled by the machine and quickly killed it, but Gavarini and Pittard continued to beat the ARM drum at internal presentations, demonstrating impressive test results with LISP.

LISP was a heavyweight language, and Apple used it to internally test new GUIs. But it was considered too bulky for embedded applications. When Apple veteran Larry Tesler saw these tests, a light bulb went on in his head.

Tesler had just taken on the Apple Newton project and needed to replace the slow and buggy AT&T Hobbit processor. The ARM chip looked like the winner. Not only was it a speed demon, but its incredibly low power consumption made it perfect for Newton’s handheld device.

Tesler set up a meeting with the ARM team and liked what he saw on their roadmap. But there was a problem. Apple was a computer company and Acorn was a direct competitor.

This set the stage for a fateful decision. The ARM staff wanted to get rid of the falling state of Acorn. Acorn’s primary owner, Olivetti, was more interested in making clones of the IBM PC. VLSI Technology, the silicon factory that made the ARM chips, needed more customers. And Apple wanted to license the chip. Spinning off ARM was in everyone’s interest.

In November 1990 a tripartite deal was reached. Apple invested $3 million in cash in exchange for a 30 percent stake. VLSI invested half a million, plus its knowledge and tools. Acorn donated all of its intellectual property to ARM and twelve employees worth $3 million. At Apple’s request, the new company was renamed Advanced RISC Machines. ARM has now been left to its own devices.

New leader

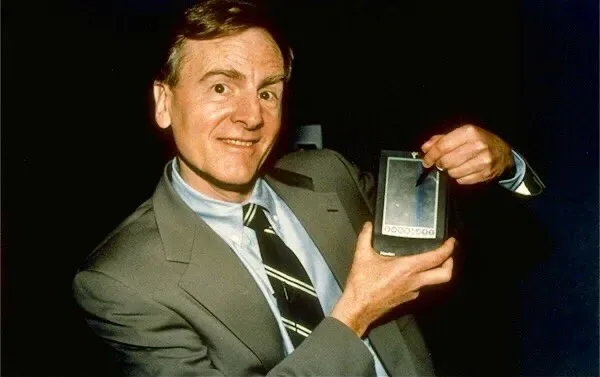

Saxby was born in 1947 in Chesterfield, England. As a child, he became interested in electrical installation, and as a teenager he started his first business repairing radios and televisions. He entered the University of Liverpool, studying electronic engineering. After graduation in 1968, his first job was to help develop England’s first transistorized TV.

After Motorola, Saxby joined ES2, a startup that was trying to develop a new silicon chip technology. ES2 created several test chips for ARM, so Saxby already knew about the company. But when asked to join ARM as its first CEO, he questioned whether he was the best fit for the job.