On Tuesday morning, Android phones in the San Francisco Bay Area buzzed with a warning that a magnitude 4.8 earthquake was about to strike. “You may have been shaking,” some messages said. The notification was seen by over a million Android users. And for some, it appeared seconds before the earth began to move.

This is not the first time Android devices have received such alerts, according to Mark Stogaitis, Android project lead for Earthquake Alerts System. But because the Bay Area is so densely populated, enough phones got the alert to be noticed by the general public. Earthquakes have historically occurred without warning, catching people off guard and leaving them without prior notice to fall and take cover. Such alerts aim to reduce the unpredictability of earthquakes, even if only for a few seconds.

Technology doesn’t predict earthquakes—no one can, and the USGS also says it doesn’t think it will be able to predict earthquakes “in the foreseeable future.”But he discovers them before people usually feel them. And experts hope that someday alerts can be sent even faster, giving people more time to avoid danger.

Time to roll

Tuesday’s Android alert was based on data from ShakeAlert, which determines when an earthquake hits the West Coast and provides information to state government agencies and third parties. And Google has taken steps to make that information more accessible in those precious seconds. First, the company has incorporated the alert into its own system, sending push notifications to people with Android phones who are in the earthquake area without having to download a separate app.

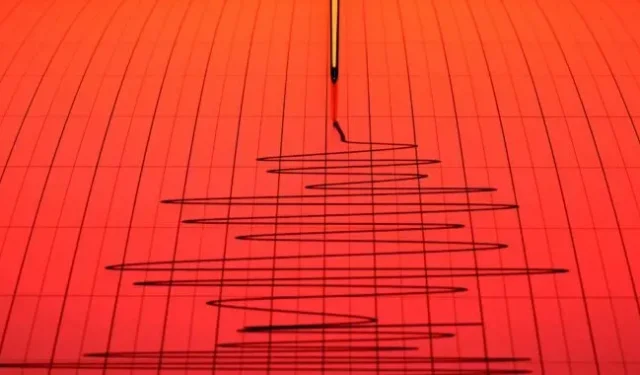

Here’s how it works: When an earthquake occurs, it sends softer seismic waves, known as P-waves, through the earth. Not everyone in the quake will feel it, but a network of 1,300 USGS sensors will. When four sensors are triggered at the same time, they send an alert to the data center. If this data meets the correct criteria, the ShakeAlert system determines that stronger S-waves are likely to occur, which can harm and harm people. That’s when warning systems like Google, an app called MyShake, or government agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency and transportation systems will interpret the data and send warnings.

There are restrictions. These S-waves move fast; the closer a person is to an earthquake, the less likely they are to receive a warning before they feel the jolt. USGS sensors are expensive and strategically located on the West Coast. (According to de Groot, there will be a total of 1,675 by 2025.) Also, the rapidly compiled magnitude measurements are only preliminary; An Android alert on Tuesday warned of an approaching earthquake measuring 4.8, but the value was later adjusted to 5.1.

Stogaytis says that phones only pick up waves when they are connected to the network and blocked. This helps to avoid confusion due to phones being jostled in bags and pockets. The long-term goal is to send signals at even faster speeds. “We are trying to determine the time [from which the earthquake starts] and the time when we will detect it and send an alert as quickly as possible,” says Stogaytis.

Equipping phones to receive signals is a cheaper and faster solution than installing larger sensors 10 feet underground in other seismic areas. But that requires people and their phones to be closer to the quake, de Groot says, and that’s not always the case. However, all these sensors – underground and in your pocket – do provide new and unprecedented warnings and critical seconds to drop and take cover, which people need to do as quickly as possible. According to de Groot, people don’t usually feel an earthquake until it’s already happened. “You are now in a situation, you are now in its center. But doing something before the shaking comes is a relatively new thing. So we’re really looking for the best way to [get people] to do it.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.